The article questions the efficacy of ERS systems in their ability to accurately detect emotions. Here at VERN AI, we question this every day ourselves. We agree with the author on many levels. (You can read it here at The Guardian).

Ned tests out Hume’s new ERS that was claiming to detect emotions, but now claims that their goal is only to understand people’s overt expressions. As with our test, Hume failed in fundamental ways (read: Hume fails because of fundamental problem with LLMs. ) It’s the engineering…

…and the many competing Psychological models of emotion.

“Put a room of psychologists together and you will have fundamental disagreements. There is no baseline, agreed definition of what emotion is."

Professor Andrew McStay, Director of the Emotional AI Lab at Bangor University

We completely agree. But Psychology isn’t the only field of study with emotion models.

(Yoda voice: “There is another…”)

VERN AI is based on a neuroscience model of emotions, which makes a more accurate and fundamentally more understandable analysis of the emotions in communication.

Because we really do care about what you mean, not just the tone of your voice. (Which is important, but not as important as the language you use).

Ned goes Hollywood too, to illustrate a point by quoting Robert De Niro.

I love Robert De Niro. I think he’s one of the best actors of our time, and of all time. He has a unique understanding of the human condition, and made himself famous by observing and mimicking behaviors. Unfortunately, Mr. De Niro is partially wrong when he says “People don’t try to show their feelings, they try to hide them.”

Of course there are many circumstances where people will hedge their communication. There are masking/covering techniques we deploy because we evolved to detect emotions and freely share them with others; and that sometimes conflicts with our goals. But we still communicate latent emotional clues we call “emotives;” often because we aren’t great at covering or masking everything. And sometimes we want people to know, though we protest too much.

We absolutely try to show our feelings. We evolved to do exactly that!

Otherwise, there would be no biochemical reward for detecting & sharing emotions. It’s important to the human being to be able to communicate their status to the social group. We get a reward for sharing new, novel information. Only when the communication of the feelings conflicts with the individual’s goals does masking and covering become an observable phenomenon.

Humans evolved to be experts at emotion recognition. It’s intrinsic to our survival as a species. In the article, Hume is put in an interesting position: Their stated goal is not emotional detection, then, what is it? Cowen says Hume’s goal is only to understand people’s overt expressions…

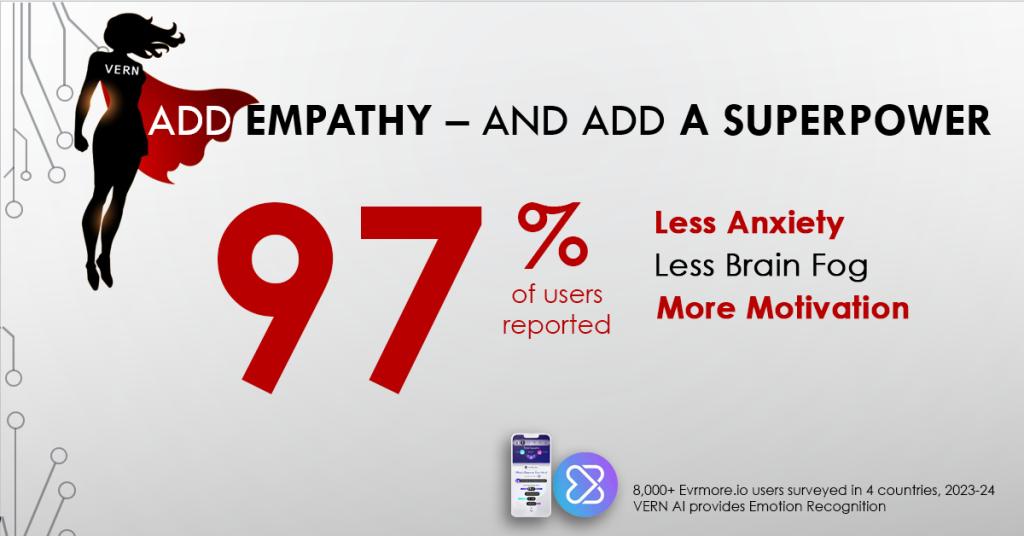

We think that detecting distinct, salient emotions is the way to help foster empathy.

Like what we have done with our partners at Evrmore.io whom we provide VERN AI to, and work with to integrate with their specific interaction models. They have over 10,000 users world-wide in four countries. Over 8,000 users were recently surveyed. Over 97% of them reported less anxiety, and more motivation. Additionally, more than half reported less negative self-talk and a better outlook on life.

Knowing the emotions, saves lives.

Interestingly, Ned gets into a topic that is near and dear to our founder Craig Tucker’s heart. Humor. And sarcasm, which is a vexing problem for any content analysis.

There are many definitions of the phenomena, but we have found that Sarcasm is a combination of humor and anger emotives. It’s an aggressive form of humor that conforms with the Incongruity Theory of Humor. Humor at its heart, is a mechanism for communicating incongruities. You cannot train a ML to find sarcasm. It’s been done, horribly, for a decade.

We applaud the study on facial movements. The study authors have found some of the same findings as we did. You can’t accurately detect emotions from facial expressions. We figured that out in 2015 and decided to focus on the language which is the way in which we code and label our world to communicate it with one another. Without a shared understanding, there is no communication of emotions. Therefore, a common language must be established.

Why do we communicate our emotions? We think it is to inform others of our internal status, our relationship to the world around us and how that comports with our goals. Ultimately, to communicate an incongruity (prediction error) that may be important to the social group.

“An emotionally intelligent human does not usually claim they can accurately put a label on everything everyone says and tell you this person is currently feeling 80% angry, 18% fearful, and 2% sad”

Edward B Kang

You’re right Mr. Kang, but a human does measure the emotional signals for relevance. There are multiple emotive signals that can be interpreted as multiple emotions depending on the context. Everyday, you encounter phrases and sentences that have Anger, Sadness, Fear, Humor and Love/Joy emotives in the same sentence. The vast majority of sentiment analysis data in the enterprise is “mixed” or “neutral,” which is because there are multiple emotional signals and multiple interpretations depending on the frame.

It’s up to the receiver to decode these signals and align them with their own personal frame.

Therefore, yes, we do understand emotional context as “mostly angry, a little sad though. And they did sound a little scared, too.” To a computer using our model, that’s 80% angry, 33% sad and 51% fearful. Let’s not have a binary bias and hate on our computer friends because they must process things in numbers not letters…(Lol)

Here’s an example, from a professional writer who is trying to communicate complicated emotions. It’s a song lyric from Bebe Rexha and Martin Garrix called “In the Name of Love,” and carries a lot of emotional impact on the receiver. (Which is what they intended).

“When the sadness leaves you broken in your bed, I will hold you in the depths of your despair, and it's all in the name of love.”

Martin Garrix and Bebe Rexha

Sentiment tools would say that is “mixed” or “neutral,” because there are multiple emotions being communicated. The VERN model finds that the message contains Fear, Anger, Sadness and Love.

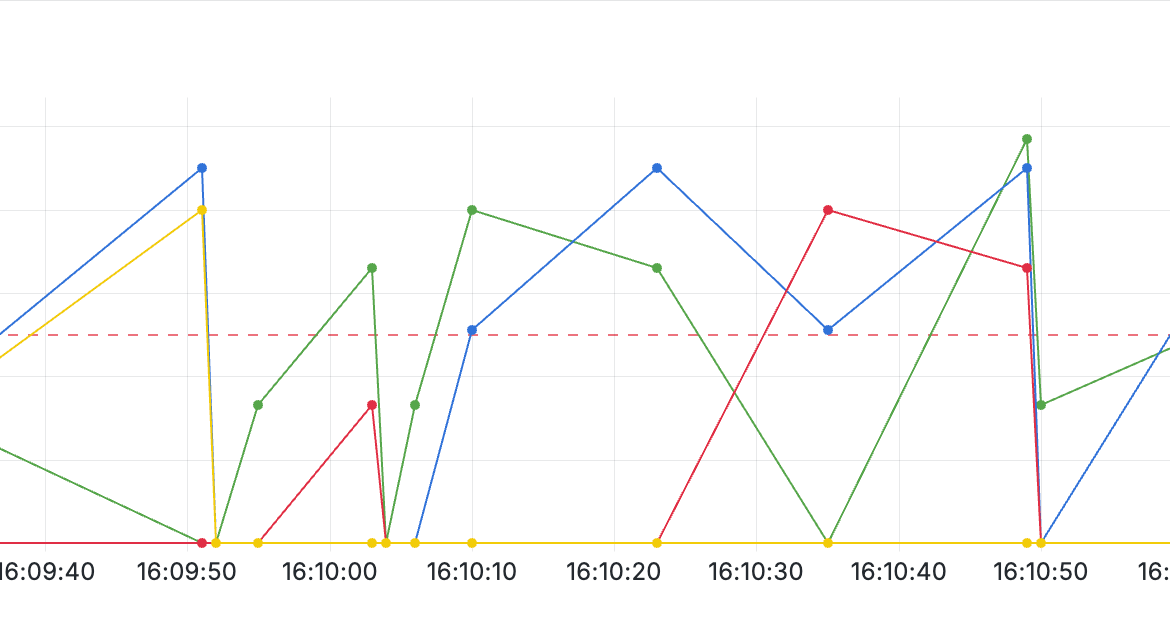

Additionally, VERN analyzes the Fear at a 90% confidence/intensity, demonstrating very high fear. A moderate level of Sadness (66%), high Anger (80%), and Love/Joy (80%) are also being communicated.

I would say that Mr. Garrix and Ms. Rexha were successful in communicating an emotionally packed message. The Greeks may recognize this as an expression of the highest order of love, or “agape.”

Ned goes on further, and does make a very great point: AI models are definitely only as good as their training data. It will introduce bias if the sample doesn’t represent the population.

If the model is derived from a machine learning process, that is. Training data is hard to come by, mislabeled, and with emotions misunderstood by psychology…impossible to make a reliable model that has external validity.

That’s why we didn’t make one by machine learning alone, or machine learning to create fundamental categories or labels. We saw the problems early on with data sets and models that introduced confounding variables. We realized after testing early ML model results, that they didn’t survive testing in the real world. (We’re talking less than 10% accuracy).

VERN AI is based on a neuroscience model, not psychology. We leveraged the work of Sir Edmund Rolls and others, that actually observed state changes in brain activity. From there, we re-conceptualized the emotions based on actual physiological phenomena.

So why all the hate for psychology? There’s no hate, it’s a wonderful scientific discipline and pursuit. Psychology informs our model too, at lower levels. The fundamental problem is one of consensus.

Psychology has a standard model of 5 emotions. Or is it 7? Depends on who you ask. Or maybe it’s 9. Or perhaps it’s Plutchik’s model of 13 (which is not compatible with neuroscience findings). Or perhaps it’s the 27 or 40 emotional models that have recently been published in journals.

Probably not any of them, it turns out. And it’s one of the reasons why emotional AI is so hard to get right. Even when you find emotives in communication, you aren’t done. We all play a game with one another, so you have to figure out the rules and how we “keep score.” Eventually those who work on Emotion Recognition Systems will understand that emotions are definitely not subjective…otherwise no one would understand them. But they aren’t objective either.

As Run DMC would say, it’s “Tricky.”

On the European Union’s AI Safety Regulations:

Safety is important, with emotions making up such an important part of the human experience. That’s why good governance is important. So is staffing your organization with subject matter experts with experience in mental health.

But the EU fumbled the ball, to use an American sports metaphor. Whereas the UK and the US understood that the communication of emotions is something humans have evolved to communicate, and therefore innovation shouldn’t be limited; the EU decided that ERS (Emotion Recognition Systems) could read your mind, and it was too risky to allow in use cases where it probably does the most good. (Sigh).

VERN AI has robust governance, oversight, and control. We will continue to validate the model and its use in the field. Our model is explainable, and you get the same answer from the same question every time.

We’re excited to read Hogman’s work on emotional synchronization. On the face, it seems to demonstrate the Sender/Receiver model that Shannon & Weaver published in 1949. That’s fascinating work and our team is excited to read the published papers.